Crum Woods Chronicle: A Vulnerable Giant

This article is part of an ongoing column called the Crum Woods Chronicle. The Crum Woods Chronicle will be periodic updates and observations about subjects related to natural history, interesting species found in and around the Crum Woods, and exciting events you can get involved in. My hope is that some of these topics will interest you, strengthen your connection to the Crum Woods, and inspire you to explore your backyard a little more often.

Natural areas do not maintain their character and quality independently, especially when they are heavily used by people and embedded in urban environments. Educating yourself about aspects of the Crum Woods that interest you and understanding how your individual use of the Crum Woods impacts it (and how you can reduce that impact!) are important steps every one of us should take.

“In the end we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand; and we will understand only what we are taught.” –Baba Dioum

A Vulnerable Giant

Kate Crowley ‘16

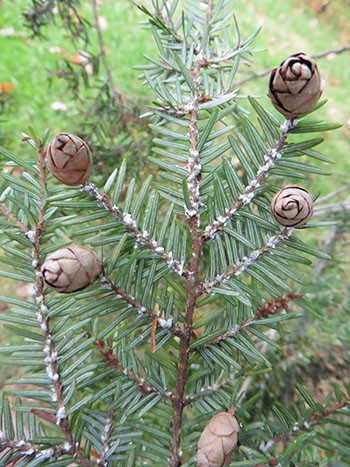

Tsuga canadensis branches droop, setting them apart from the other pointed trees in the pine family. photo credit: K. Crowley

Most associations with the name “hemlock” are probably not positive. You might recall that Socrates drank hemlock tea as his preferred method of death following his sentencing. However, this article is not about the poisonous hemlock plant, (which is also present in our area), but rather the benign hemlock tree.

It turns out the hemlock tree follows the oft-repeated pitfall of common species names—it is named after another plant, not for its genetic similarity, but rather for some perceived superficial similarity. In the case of hemlock trees, it is because their crushed foliage is said to resemble the smell of the hemlock plant.*

Tsuga canadensis planted by President William Howard Taft on Commencement Day in 1915. photo credit: R. Pineo

Hemlock trees actually include a number of different species, native to areas as diverse as North America, Japan, and China. Four species are native to North America, including: eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana). All are members of the pine family.

The James R. Frorer Holly Collection was planted along the edge of the Crum Woods in 1975. photo credit: Scott Arboretum Archives

In the 1930s, John Wister (first director of the Scott Arboretum), planted thousands of hemlock tree saplings on campus and in the Crum Woods. He believed they exemplified the beauty of Northeastern trees. Additionally, “Part of the reasoning for planting so many hemlocks was to create a habitat like the hemlock-mixed oak forests of the Poconos for botany students to study,” said Crum Woods Restoration Assistant Mike Rolli.

Eastern hemlock, the state tree of Pennsylvania, usually grows from 40 to 70 feet (12-20m). Hemlock tree branches droop, setting them apart from the other pointed trees in the pine family. Today, both eastern and carolina hemlock can be found on campus and in the Crum Woods; two other species native to China and Japan can also be found on campus. A number of hemlock trees border Scott Outdoor Amphitheater, several dot the area just south of Sharples, and an especially impressive specimen can be found outside the President’s House.

Surprisingly, the purple tree near the fieldhouse tunnel is also a hemlock tree! The tree turned temporary art installation is a weeping variety that looks very different from its larger relatives.

Eastern hemlocks are especially long-lived trees. It takes 40 years before they even begin to produce seeds. Trees can live up to 1,000 years, but many of the hemlock trees on our campus and in the eastern United States will not live a full and natural life. An invasive parasite, called the hemlock woolly adelgid, has infected more than half the native range of eastern hemlock.

Turn over any branch and look for white “woolly” spots to discover hemlock woolly adelgid. photo credit: K. Crowley

The woolly adelgid is an insect, similar to the aphid, and originated in southern Japan. In its native habitat, the woolly adelgid lives in relative stability with Japanese hemlock trees that have developed a resistance to the parasite. However, the eastern hemlock and carolina hemlock show no resistance to the adelgid.

You can find the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) on many hemlock trees on campus or in the Crum Woods. Simply turn over any branch and look for white “woolly” spots. These woolly spots are actually egg sacs. Once the HWA hatch, they will insert their mouth parts into the hemlock needles and suck out nutrients, damaging the tree, and eventually killing it.

The spread of HWA has mostly been restrained by cold northern temperatures, although they appear to become dormant, rather than actually die in cold temperatures. There are concerns the insect is evolving resistance to colder temperatures. Additionally, climate change could make previously unfavorable areas part of the HWA’s range.

Insecticides and horticultural oil products are control options, but are not practical for widespread forest use. Various forms of biological control, including insect predators from North America and Japan, are currently being researched and undergoing field tests.

On our campus, the arboretum aims to use some type of pest management on each hemlock tree twice a year. “The treatment of choice lately has been a dormant spray of horticultural oil. This is a product that basically suffocates the crawlers and eggs by coating them, clogging their spiracles and interfering with respiration,” said Bill Costello, Integrated Pest Management Coordinator.

The small size of our campus makes this kind of treatment feasible for highly accessible trees, but hemlocks in the Crum Woods are not treated as a result. Another benefit of horticultural oil is that it doesn’t persist in the environment or threaten other desirable insects, like pollinators.

The hemlock trees of the eastern United States have a very uncertain future. What is clear is that our woods would be a lesser place both biologically and aesthetically without this regal tree.

*Please resist the temptation to confirm this independently

http://www.hrt.msu.edu/assets/Faculty-Photos/Cregg_Bert/hemlocks.pdf

http://www.arborday.org/programs/nationaltree/hemlock.cfm

http://www.nps.gov/shen/learn/nature/eastern_hemlock.htm

http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/pdfs/HWA-FHTET-2014-05.pdf

James Hughes

Posted at 13:53h, 19 JanuaryNo comment about the Chinese Hemlock Tsuga chinensis that is resistant to our woolly friend?

Bill Costello

Posted at 12:50h, 27 JanuaryYes, the Chinese Hemlock is resistant to Wooly Adelgid infestation, but I think the main focus of the blog was to highlight the attributes and trials of the native hemlock.