Guest Author: Moss Graves, 2025 Summer Education Intern

Lycoris squamigera – surprise lily

I met a gardener while on a summer stroll last year, and he laughed after I asked about how his humid day of gardening was going, “everything is great, I get to work with naked ladies all day!” He was referring to Lycoris squamigera of course, which has many common names including, naked ladies, surprise lily, resurrection lily, and hurricane lily. Witty humor like this carries us gardeners through the dog days of summer, accompanied by the blooms that award our labor. L. squamigera is a late-summer flowering herbaceous perennial in the Amaryllidaceae family, that magically erupts its long, anguiform flower buds from the earth in late July. The plant surprises us with showy pink and white iridescent flowers just a few days later that develop peculiar digits from its floral buds. This magic show carries on while the surprise lily is entirely absent of foliage, surprising us with flowers right when we thought the plant was dormant. Underground, the bulb is quite the opposite, burgeoning fantastic fertile flora.

The mystery of this incredible species becomes even more fascinating when exploring the morphology of this unusual geophyte. The show starts in spring while the other ephemerals bloom. L. squamigera appears idle with only its chlorophyllic foliage. Due to this, it can be easily confused as flowerless Narcissus spp. (daffodil). A novice gardener may accidently pull this plant out or chop it back, thinking they are simply completing another garden chore on their todo list. However, it is important to differentiate the plant before making this mistake, as these photosynthetic leaves are the harbinger for L. squamigera’s summer magic trick. Surprise lily’s foliage is strap-like, has a bluish hue, and is more rounded at the tip than a typical daffodil. Keeping vegetation intact until they brown and shrivel in late spring helps the resurrection lilies store energy in their bulbs to send up tall, leafless stalks topped with 6-8 fragrant trumpet flowers in late summer. This unusual growth pattern is an adaptation to survive in climates with wet springs and dry summers, which is comparable to our zone 7 climate, and to their native habitat of Japan and China. Although this is the hardiest of all of the Lycoris species and they are well adapted to many types of soil, surprise lilies do not like to be over-watered in the dormant months of September–Feburary, so planting them on a slope, or in coarse soil is ideal. At The Scott Arboretum & Gardens, they can be seen along Magill Walk, speckled through the Terry Shane Teaching Garden, and scattered along the Cherry Border’s sidewalk on Cedar Avenue where the soil is fertile, moist, and well-draining and there is full sun to partial shade.

Angelica gigas – Korean angelica

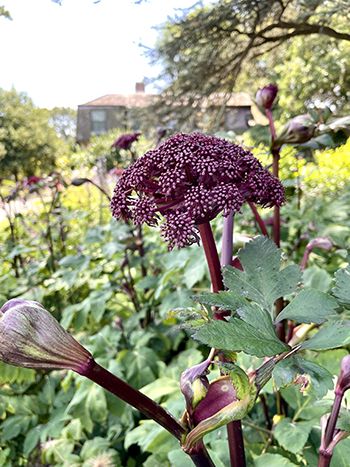

Architectural garden giants like Angelica gigas are awe-inspiring beacons for pollinators as well as young children admiring them at half their height. How can a plant grow so tall, around 5-6 feet, in such a short amount of time? The fascinating genetics of A. gigas explains how these quiet giants make such a loud impact in our gardens. Korean angelica is a biennial, meaning it is vegetative in its first year then flowers and dies in its second year. This two-year life cycle is relatively short, so the plant must develop robust anatomy in order to capture as much energy as possible for the production of seeds in autumn, securing its lineage. A. gigas prefers full sun and rich soil in order to develop tall stems and large leaves to support the nutrients needed for their gargantuan structure, glorious blooms, and hundreds of seeds. The first year plant is relatively short and stores sugars in their thick taproots which is used as energy for their second-year fruiting bodies. Biennials rely on self-sowing to continue their colonies, and should be left to seed in the fall, in order to see them return the next year. By the nature of this, they may pop up in places you didn’t already plant which could be an unexpected joy.

The leaves of Korean angelica are bold and broad, with striking serration situated on deep purple stems.The flower structure starts with bulbous pods of a similar shade, that explode into nectar-rich, burgundy, hemispherical umbels, that flower for a period of 4-5 weeks. The inflorescence attracts many types of pollinators including bees, butterflies, and wasps; dancing around the luscious flowers in synchronicity, all feasting on the same treat. The flowers are additionally excellent for longevity in cut-flower arrangements and dry into marvelous seed capsules. At The Scott Arboretum & Gardens they co-habitate with Acanthus caroli-alexandri (bear’s breeches) in the Entrance Garden along College Avenue, sharing a similar color palette and upright habit.

Iris domestica – blackberry lily

As a winter garden enthusiast, I am usually thinking about winter seed displays… even in August. Seed pods eternalize the beauty of a specimen’s unique reproductive anatomy, to admire and learn from for more seasons than their lifecycles endure. The Iris domestica (blackberry lily), contributes to the eternal wintery display of textures and shimmering dry leaves. After flowering, this plant produces pear-shaped seed capsules that hold on to their dried pericarp and recurve at maturity, to expose an abundance of glossy, black seed clusters giving it its name, “blackberry.” At a glance, I. domestica is hard to differentiate from the tasty fruit we are used to seeing on the borders of deciduous forests and in our grocery stores. While not edible to humans, birds love the seeds of blackberry lilies and disperse them. Despite its name “lily” and its unusual Rubus-like seeds, this plant is not genetically related to any of those species. In fact, Iris domestica is part of the Iridaceae (iris) family. Knowing this now makes the specimen’s features, its fan-shaped leaves and rhizomes, more understandable, but still makes my head scratch.

This plant is equivalent to a “franken-plant” if I’ve ever seen one. The corolla and immature seed pods resemble a diminutive Lilium lancifolium (tiger lily), with traffic-cone-orange petals lined with crimson speckles, but has the foliar interest of an iris. The bloom period is short, but occurs in successions through the months of July and August, providing long color. Deadheading will prolong the bloom period even more. It prefers well-drained, fertile, loamy soil, but does fine in clay soils. This plant can be invasive and naturalize in parts of eastern North America, so it is encouraged to harvest the seed heads. Use the pods in winter wreaths and floral displays to add an unusual element to your holiday decor. The horticulturalists at The Scott Arboretum & Gardens make an effort to maintain this plant throughout the seasons within the Terry Shane Teaching Garden where it is nestled between Acalypha wilkesiana ‘Haleakala’ (copper leaf). They remove the spent flowers before the seed pods develop to prevent the spread of this plant though the garden to prevent self-sowing.